Why is your sense of smell so important when it comes to cooking?

Harold McGee is a food legend. He brought food science from the lab onto cooks’ bookshelves and inspired a generation of chefs. In his latest book, aptly named Nose Dive, McGee takes a leap into the universe of smells, as Susan Low discovers…

Ever wondered how onions can go from off-puttingly pungent in their raw state to sweetly enticing when cooked? Or why fruit smells so come-hither? Did you know that eating lots of fenugreek can change your body odour, or that terpenoids, the molecules that give cannabis its distinctive whiff, can also be found in citrus peel? These are just some of the subjects touched on by-the-by in Harold McGee’s latest 600-page tome, which reaches beyond the world of food and takes us through a history of the universe in smells. Like his other books, it mixes chemistry, physiology, psychology and biology, adds good dollops of humanity and humour, and seasons it all with an infectious sense of wonder.

McGee has been an authority on the science of what we cook and eat for more than 40 years. His masterpiece, which holds pride of place on any self-respecting food geek’s bookshelf, is On Food & Cooking: The Science & Lore of the Kitchen. First published in 1984, it answers just about any question you’ve ever had about food (plus many you haven’t).

The science of smells

McGee doesn’t tend to take a casual interest in things. He has spent the last 10 years researching and writing Nose Dive. In it, he turns his attention to our sense of smell, introducing the concept of the ‘osmocosm’ – a conjunction of osme, the ancient Greek for ‘smell’, and cosmos. “I coined the word,” McGee explains in our Zoom interview, “because I kept finding, as I was writing the book, that I was talking about ‘the universe of smells’ and I wanted something that could stand for that concept. I also just like the way it sounds.”

Smell has tended to be less valued than the other four senses. As McGee writes, “Despite its reputation as one of the lowest of human faculties, smell has the power to engage us with the world around us, to reveal invisible, intangible details of that world, to stimulate intense feeling and thought: to nudge us into being as fully and humanly alive as we can be.”

The importance of smell has become particularly poignant during the pandemic. “One of the losses of the past year has been the sense of smell; of your friends, and of familiar places,” McGee says. Anosmia – the loss of the sense of smell and taste – and parosmia (smelling ‘good’ smells as ‘bad’ and vice versa – see overleaf) are known side effects of Covid infection. Ironically, while researching Nose Dive, McGee lost his sense of smell for weeks following a sinus infection.

A stellar career

McGee didn’t set out to be a food writer. He began studying physics and astronomy, but his heart was in writing so he switched to literature. He taught writing and poetry for a while, but soon changed tack. “I started writing about the science of everyday life, and cooking,” he explains. “This was the mid-1970s when food wasn’t really a thing yet. But what fascinated me was the pleasure that we get from eating and drinking – and flavour, in particular, as this mysterious experience that made it all worthwhile.”

But when food really did become a thing, he was on hand to apply the science, working with chefs such as Heston Blumenthal and Spain’s Ferran Adrià at the height of the 1990s molecular gastronomy boom.

Kitchen experiments

“I’m a believer in experimenting. I almost never make a dish the same way twice because I always want to find out what’s going to happen if I do it another way,” he says. “I think that’s the best way to cook: to take it a little further than you did the last time to see what happens. Maybe it’s better, maybe it’s not…” The other key thing to do in the kitchen, as McGee has learned during his decade-long nosedive into the world of smell, is to get in there and sniff. “The air around us is filled with volatile molecules. These are real things that are actually detectable and are a much more direct experience of our world than sight or hearing are. These are actual little bits of the world that make it into us and become part of us for a moment. So take time to realise that and to be amazed by that fact.”

How to improve your sense of smell

As with any other skill, it’s possible to improve your sense of smell. “Studies have found significant differences in the brain structures and activities of trained perfumiers and wine experts,” writes McGee.

So how can you get your nose working better? “You can improve your sense of smell by putting yourself through little exercises. Pick up the spices that are going to go into an Indian dish and smell them from the bottle, then again when you toast them, noticing how the smell changes.” Wine professionals use kits with tiny vials of aromas –learning to identify each one develops olfactory acuity. For people whose sense of smell is impaired from injury or disease (including Covid), AbScent has advice and resources, including kits and Skype tutorials for smell training, which they describe as ‘physiotherapy for the nose’.

Nose Dive: A Field Guide To The World’s Smells by Harold McGee (John Murray £35) is out now

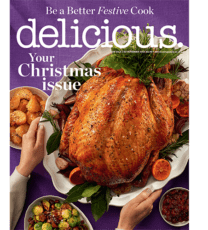

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter