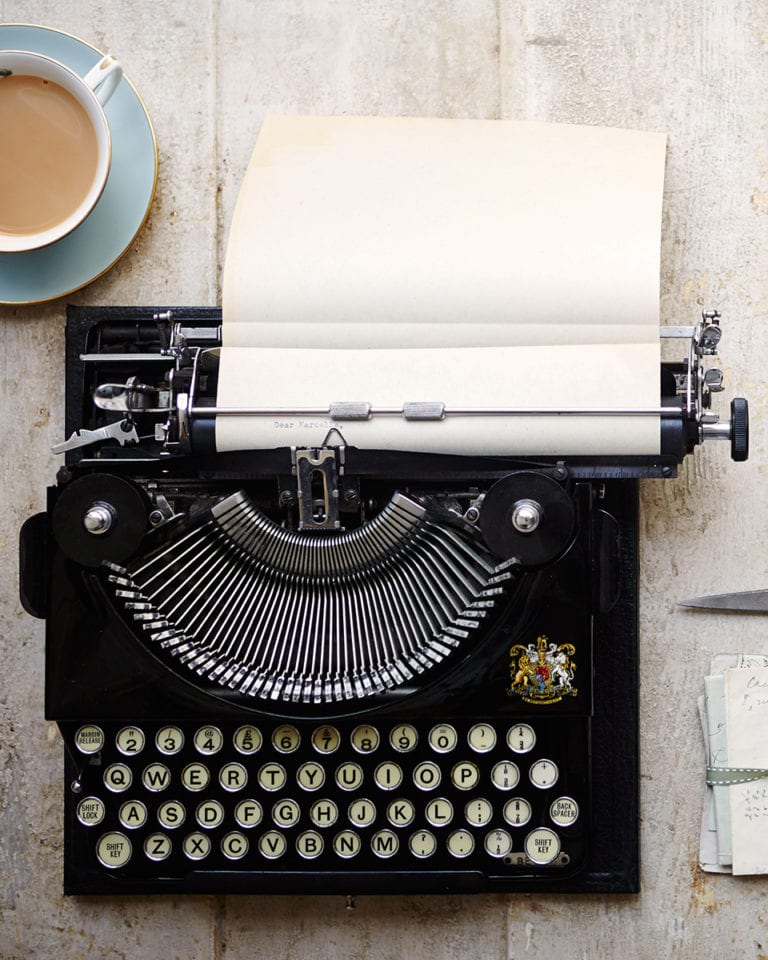

Letter to my food hero

Letter writing is an endangered art. In the rush to email, text or tweet, sitting down to put pen to paper is a rare indulgence. To change all that we invited three food writers to pen a note to someone – living or deceased – who’s inspired their cooking. It’s not something that can be done in 140 characters or fewer, and it’s so much better as a consequence.

Find out who Thane Prince, Ruth Reichl and Lucas Hollweg write to, plus recipes from each.

Thane Prince writes to… Marcella Hazan

Marcella had a reputation for being forthright and exacting – a New York Times obituary admiringly described her as “a tough biscotti with a raspy voice, who didn’t suffer fools gladly”.

One of the foremost Italian food writers, she was born in Emilia-Romagna in Italy in 1924. She earned a doctorate in biology and natural sciences before marrying wine writer Victor Hazan and moving to New York in 1955. She’d never cooked before she married but taught herself using Italian cookbooks. She began giving cookery lessons in her apartment and contributed recipes to The New York Times. Her first book, The Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking (1973), has become a standard text on the subject. She went on to write five more books before she passed away in 2013.

Here’s Thane’s letter:

“Dear Marcella,

It was over 30 years ago that we met and talked, but so much of you has followed me through my cooking life. You were three years younger than I am now, grey-haired with smiling eyes and accompanied by your husband Victor who was your biggest critic and inspiration. I saw you then as old. What little I knew.

You, like me, came to cooking late and out of necessity. Wanting to eat well you realised you would need to learn to cook. Self-taught, you became one of the leading exponents of the food of your native Italy. When I taught cooking in Italy I always kept your books at my side, your voice in my ear. You loved both simple food and the more complex, but it instilled in me a discipline. Not for you the handful here, handful there school of thinking. Your soul, rooted in the food of your Italian childhood, knew instinctively that certain pasta shapes best served certain sauces. It was you who taught me that fresh pasta is different from, not better than, dried pasta and indeed that most often dried pasta is what you will be cooking. But not overcooking. The pasta must be firm, you told me, introducing me to the term al dente, meaning firm to the bite.

But you cooked your vegetables until tender and full of flavour. It’s because of you that I put onions into a cold pan and cook them slowly. I mash my garlic with a knife, using the garlic sparingly, and I embrace simple combinations: lemon with chicken, pasta sauce with herb-scented oils.

They say you should never meet your heroes… They lie. I’m grateful I had the chance to meet one of mine.

Thane”

Here’s Thane’s recipe, a classic spaghetti vongole, inspired by Marcella Hazan.

Thane says: “Possibly my favourite pasta recipe, this simple dish depends on the correct cooking of the pasta, the melting and sweetening of the onion and the judicious use of chilli. I use shallot instead of onion, preferring its sweetness, but you may choose either or both. If you do add garlic, add it once the shallot has softened to prevent it burning and becoming bitter. I also add one large skinned tomato but this is optional and can be the subject of heated discussion among purists.”

Lucas Hollweg writes to… Margaret Costa

Born in Zimbabwe in 1917, Margaret studied French at Oxford, then, in the years after World War II, combined a writing career with cooking for private dinner parties.

She was one of the founder members of The Good Food Guide and, in 1967, became cookery columnist for The Sunday Times Magazine, where she remained for years. Her only book, the Four Seasons Cookery Book, was published in 1970. The same year she opened Lacy’s restaurant, known for its adventurous and controversial menu. She died in 1991.

“Dear Margaret

I was barely three when your Four Seasons Cookery Book was published; I only knew of its existence when it was reprinted in the mid-1990s. And yet, a decade and a half later, when I came to write a book of my own, it had imprinted itself in the back of my mind – a model of what a cookbook should be.

Looking at it now, it hasn’t really aged. Yes, there’s the odd recipe that gives away its vintage – many flans, perhaps a bit too much pineapple. But the vast majority are timelessly good: sorrel and lettuce soup, potted crab, braised lamb shoulder, mussels poulette, hazelnut ice cream and Polish walnut tart, gnocchi, omelette Arnold Bennett, osso buco, rhubarb fool, rillettes, lemon caraway cake… I would happily cook and eat everything on that list every day.

As Brenda Houghton, your editor at The Sunday Times, once told me: “Margaret was greedy. You always knew her food would taste good.”

You wrote and cooked in a flat so tiny that the kitchen table served

as both work surface and desk (a problem, incidentally, that I know only too well), and confessed that you would often cook only one course yourself, serving up some smoked fish, a perfectly ripe cheese or

a plate of sugared apricots to complete the meal. The key to good food, you said, was in the buying as well as the cooking: “You have to take trouble at some point, but that can – and should – be in the shops as much as at the stove.”

At a time when most British mealtimes involved a samey rotation of roasts, pies, mixed grills, eggs and fish and chips, you championed ingredients that many still viewed as suspiciously foreign. How many people, I wonder, did you inspire to scoop the flesh from a ripe avocado, add a splash of Pernod to their fish stew or even grind their own black pepper? How many, because of you, had their first thrilling taste of garlic, fennel or olive oil?

That passion for eating well was always your starting point. Where most cookbooks had chapters divided into soups, starters, mains and desserts, yours was a joyful celebration of seasonal ingredients and dishes – asparagus, rhubarb, salmon, lamb or pancakes in spring; trout and mackerel, crab, peaches, herbs or ice cream in summer. Nobody had arranged things that way before, but it established a blueprint many food writers still follow to this day.

Your writing was never grandiose, though it was underpinned by a quiet erudition and firmly held opinions. “Chicken,” you wrote, “has, through intensive breeding, become the cheapest, most commonplace and most uninteresting of everyday foods.” Every essay – each one a paean to your chosen ingredient – included extra recipes and tips to guide the reader: how to dress strawberries with macaroons or “a cardinal’s cloak” of raspberry and redcurrant purée; how to make fish stock; which olives to use in a daube and which with braised duck.

Above all, you communicated your love and knowledge of food with an enthusiasm that reached out beyond the page, gently encouraging people to the stove. That, more than anything, is your true food-writing legacy, and one for which I and many others owe you a debt of gratitude.

Cooking, you once said, is “a kind of loving – an expression of affection”. You knew the happiness that comes not just from making good food for others, but from the very act of cooking itself. It is, you wrote in your book, “the most soothing and restful of occupations. To beat and baste, to peel and chop and slice, to taste and test and stir and skim is therapy, what in the old days they used to call joy.”

Even five decades after your book was first published, I can’t think

of a better reason to spend time in the kitchen.

Thank you for being an inspiration.

Lucas”

Here’s Lucas’ recipe, for spinach gnudi, inspired by Margaret Costa.

Lucas says: “In the late 1960s, ricotta and parmesan were scarcely available. Margaret was aware not everyone would have access to them, so made her recipe for gnocchi verde using cream cheese and unspecified ‘grated cheese’. This is an update: gnudi are a lighter version of gnocchi that have become popular in recent years. You’ll need to start them a day in advance.”

Ruth Reichl writes to… MFK Fisher

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher was a formative voice in American food writing. Born in 1908, she was a prolific writer, penning some 27 books including two novels.

The words ‘witty’ and ‘wise’ were frequently used to describe MFK Fisher’s writing. She had a killer sense of humour and vivid voice all her own, one that sounds contemporary even to modern ears. In her later years, she continued to write about food from her house in California wine country, despite having Parkinson’s disease. She died in 1992.

Here’s Ruth’s letter to MFK:

“Dear Mary Frances

“Why not come for lunch?” you said the first time we met.

I worried over that for days. What would you feed me? Would it

be difficult? Caviar, I thought, remembering all those meals you had described in France, or perhaps a soufflé. Surely I’d spill whatever it was and make an enormous idiot of myself.

In the end, however, you fed me a lovely bowl of pea soup and buttered bread. Was there perhaps a little salad too? In that Seventies era of awkwardly self-conscious food, it was the most eloquent meal. Supremely simple, it was of the place and of the moment, and I thought, “If Mary Frances Fisher eats like this,

I can too.” Now, every time I go into the kitchen I remember that little meal, and hear you saying, “I like to eat good stuff.”

There was wine too, and I remember asking if you considered yourself an expert. You snorted. “I know good from bad,” you said tartly, “and that should be enough for anyone.” Another lesson.

But the biggest lesson was the one I’d already gleaned from your books. It was about paying attention, savouring your own life and being grateful for the small things that often go unnoticed: the splash of water in a glass, the scent of citrus as you slowly peel an orange, the flash of colour as a bird flies past your window.

But of all the advice you offered me – and there was no lack – the piece that had the biggest impact was not about food or cooking. It was about writing. “You’re spending too much time aiming for perfection,” you said. “You’re polishing every word. You should get a job at a newspaper. You need to let your ego go, write fast and hard knowing that the words you write today will be wrapping someone’s fish tomorrow.”

Like everything you had to say, it was to the point. Keep it simple. Work hard. Pay attention. Love what you are doing. And for that – and so much more – I am grateful.

That was the first of many visits, and each time I returned to your little house among the tawny hills of Sonoma, I tried to bring you something special. I think perhaps this cheesecake was the gift you liked the best. It was its simplicity, you said, and that it reminded you of the time you’d spent in Spain.

Ruth”

Here’s Ruth’s recipe, burnt cheesecake, inspired by MFK Fisher.

She says: “I first tasted this cake in a little pintxo shop in San Sebastián in Spain, and was blown away by both the texture and the flavour. I kept going back, again and again, trying to figure out what makes it so special. I realised that the magic is in the simplicity of the ingredients, and the fact that in place of the usual vanilla, this cake gets its flavour from the toasty burnt edges.”

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter