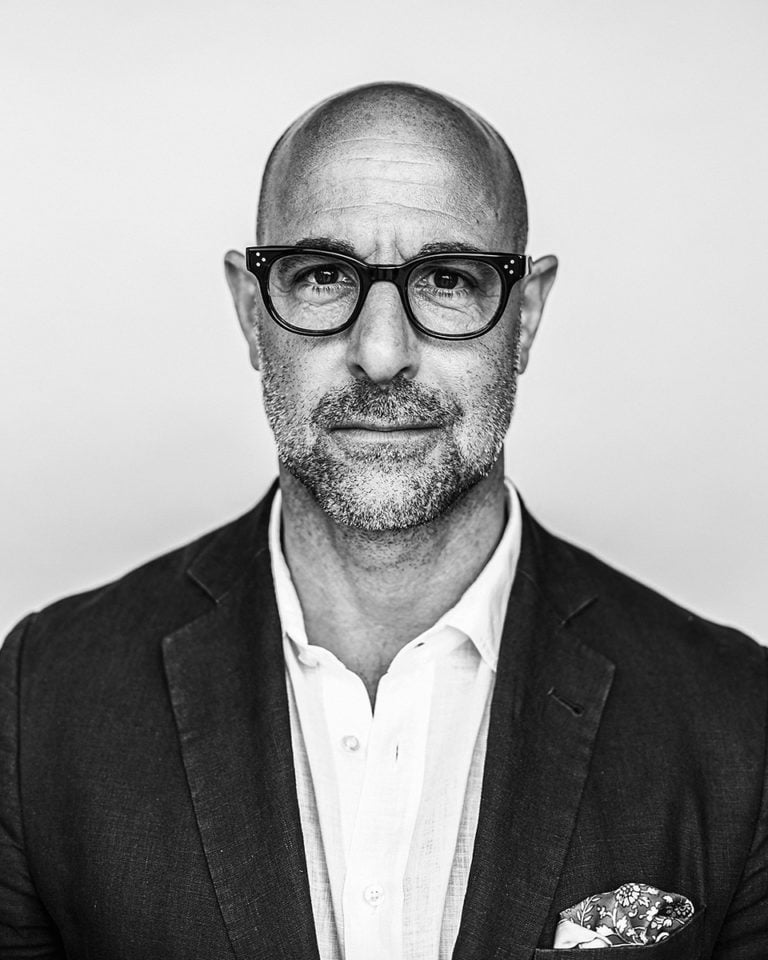

Diana Henry meets…Andrew Wong

In her new series of interviews for delicious., Diana Henry meets Andrew Wong and learns how the British-born chef rediscovered Chinese cooking.

When is a restaurant meal more than a meal? When it’s also an experience, an education, when emotion is involved. These are central to the cooking of Andrew Wong, and the reason his two-Michelin-star restaurant is high on food lovers’ wish lists. Yet he’s also on a mission that will never be finished…

It’s my birthday, so I’m sitting in A Wong, a Chinese restaurant in London and a place so special that I come here only for celebrations, a family lunch at Christmas or for dinner when I’ve finished writing a book. The menu is a work of poetry and creativity – one of the desserts is described as ‘coconut water ice, mulberries, fermented coconut, yoghurt and mochi’.

And then the food starts to arrive: Shanghai dumplings, clouds of warm pork with ginger-infused vinegar that you have to lift carefully so as not to pierce the paper-thin dough; soft ‘smacked’ cucumber with salty pearls of trout roe and hot chilli; sweet Cantonese honey-roast pork with wind-dried sausage and melting shavings of foie gras. This is food I could never cook, food that takes me to a place I’ve never been and which it is difficult to understand.

A complex cuisine

The ‘A’ in A Wong isn’t for the chef, Andrew, but to honour his parents, Annie and Albert, who owned this restaurant (and two others) when he was a boy. He’s still like a boy as he sits cracking jokes and being impish, but his head is full of serious matters like how to manage, in one restaurant, to convey the taste of China, a country that has 14 international borders and has been ‘soaking up’, as Andrew puts it, influences from other countries for 3,000 years.

The food Andrew serves here – complex, elegant, distinctive – is often described as ‘modern Chinese’, but he prefers it to be called simply ‘Chinese’. “To say it’s modern Chinese food is to suggest unmodern Chinese food is inferior, and that’s not the case.”

It’s not like the food you’ll be served in most of the restaurants in Chinatown, or even in the best restaurants in Hong Kong, because it’s the product of Andrew’s research, his travels to China and the work he does with his team of chefs and Dr Mukta Das from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). He may be laughing as he talks about being kicked out of Oxford University after failing his first year exams (twice) but only serious application and thought can produce this kind of food.

“Andrew’s aim, ultimately, is to get his customers to engage with China, to taste it. He is a chef but also an educator." — Diana

A family business

Andrew was an unlikely candidate for becoming a chef. He started working in the family business when he was just eight years old, coming in after school to wash glasses and fold napkins. “My father could never understand why I might want to play football or see friends after school. For him, the restaurant wasn’t a way of making a living but a way of life.”

Apart from school dinners, the only food Andrew ate while growing up was Chinese. “At that time, in the 1980s, Chinese food wasn’t supposed to be diverse, it was meant to be uniform. Always Cantonese. My dad had five or six friends who also owned restaurants and they all had the same dishes on their menus. They even used the same English translations for the dishes.” Andrew often had to serve the ‘sizzling’ dishes, which were a thing in Chinese restaurants at the time, and would go home reeking of black beans.

His work was very much a duty, not a love, but he clearly soaked up the family work ethic. His parents initially wanted success for him in another area. After he left Oxford, his dad was adamant that he study law. Andrew rolled up on the first day to see his fellow students carrying suitcases. “I asked them what the suitcases were for and they said ‘books’, so I just got the tube back to Victoria. There was no way I was going to like a course that required that many books.”

After that he fudged the truth a bit, signing up for social anthropology at the LSE. “There was a module called law and anthropology, so I thought that was good enough to satisfy my dad. I did finish that degree,” he laughs.

“My father could never understand why I might want to play football or see friends after school. For him, the restaurant wasn’t a way of making a living but a way of life” — Andrew

Travelling and learning

When Andrew’s father died he had to take on the family business while

studying at university and chef school. In 2005 he made his first trip to

China to start learning more about the food, but it wasn’t like going home. “I might as well have been in Outer Mongolia!” he says. “The only time I felt grounded was when I was cooking, especially when I was in Sichuan. People would say that I understood the food, that I knew when a dish was perfectly spiced and seasoned.”

Over successive visits he amassed huge amounts of knowledge. “It was still arrogant to think I could bring the whole of China back to London. But I had one huge advantage in being British-Chinese. I was able to understand what diners here would appreciate. Desserts were difficult. There is such a dissonance, even now, between what is eaten in China and Hong Kong and here. Chinese jellies are quite savoury, not what people here think of as dessert.”

What he tries to do at A Wong is “paint a picture” – using Chinese history, stories and anthropology to create dishes. “I do spider diagrams. I start off thinking in terms of opposites, then I might add ingredients I know were used at specific periods in Chinese history. That’s the beginning and the dishes evolve.”

I wonder how his team of chefs, who come from all sorts of backgrounds, can help him develop Chinese dishes. “Different food cultures have similar elements. Dumplings, wraps, pastries… You find these the world over as well as in China. So you can consider a filo cigar stuffed with meat and feta and wonder what, in China, could replace the cheese.” This all sounds very cerebral, but it also comes down to practicalities and pleasure. “As chef Pierre Koffmann says, the difference between good cooking and bad cooking is usually a bit of salt.”

“I push every day because I’m discovering — and self-discovering too… Cooking has connected me to my culture.” — Andrew

Telling stories through food

Andrew has grappled with the idea of Chineseness, authenticity and cultural appropriation. “Then I had a conversation with Dr Das at SOAS, and she said: ‘Andrew, once you start that conversation it’s a race to the bottom. Who did what first isn’t a relevant conversation.’ China was the hub of international trade because of the silk roads – the trade coming in from India and the Middle East. It was a huge sponge that soaked up many influences. Once you accept that you can begin to move forward.”

Andrew grew up with conflicting ideas about China. Through the 1980s and 90s, Chinese friends would tell him he was mad to want to travel to China, that he’d be abducted or worse, and both his grandfather and father were negative about it. Then his grandfather changed. “He would say, ‘Andrew, China is going to be the next superpower,’ and my father would get cross when we didn’t speak Chinese at home.”

Andrew’s aim, ultimately, is to get his customers to engage with China, to taste it. He is a chef but also an educator. It’s why he has a tasting menu – A Taste of China – as well as an à la carte one. He longs for diners to order different dishes every time, not to stick to the ones they know. He almost wants to tell them what to eat to enlarge their experience. “Meals here are about celebration – that is what is important in food – and respect through that celebration. I want to relay stories and history and bits of my own journey through food.”

I tell him that my eldest son, now at an age where he can appreciate such things, was moved to tears when we last ate here. It wasn’t just because of the flavours or the mouth feel; he was simply touched that human beings could produce this, that they cared enough. Andrew smiles. The restaurant is fulfilling his aims.

Has he come to terms with being a chef? “I push every day because I’m discovering – and self-discovering too, in a rather selfish way.” He’s chuckling again, then turns serious. “Cooking has connected me to my culture. And there has to be a point at which you have to mean what you do.” With that, he heads off to the kitchen to check on the 1,500 dim sum that are made every morning.

A Wong is in London SW1; to book, visit awong.co.uk

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter