Cooking with dementia, vegan burgers and going to seed: listen now

In this week’s episode, I meet the future foods man who’s the first to give the beyond meat burger a home of its own, the B&B owner who’s quietly converting her guests to living lightly on the planet and best-selling author, Wendy Mitchell, whose memoir about dementia has plenty to teach us about how to enjoy our food.

First up, delicious. editor Karen Barnes tells me why it’s important to make mistakes when cooking. Otherwise, how else would we learn? Look out for a feature in the May issue where the team share their shameful mistakes.

I talk to Ross Forder about plant-based proteins and, in particular, his company Halo Burger. He tells me why he quit his high-flying job to pursue a passion for vegan burgers.

Next is Vicky Radtke, from Starnash guest house, who not only eats seasonally and locally but also serves her guests the very same. She tells me about how she lives off the land in East Sussex. Want to hear more from Vicky? Scroll to the bottom of the page where she explains why ‘going to seed’ is no bad thing for the veg patch.

Wendy Mitchell was diagnosed with dementia in her late fifties, her response was to write about it; her blog was written into best-selling book, Somebody I Used to Know, in 2018.Wendy tells me how dementia has affected her way with food.

I chat to Monica Galetti about how she mentors and judges on Masterchef: The Professionals and how she is on the hunt for the 2020 S.Pellegrino Young Chef.

Then to Bangkok, to meet with Ian Kittichai who tells me what it was like to serve David Beckham at his restaurant Issaya Siamese Club. He tells me what differs in his food and why the celebs flock to eat it.

Finally, Liv from the food team tells me why everyone should play with their food… listen here:

You can find all our podcasts in the delicious. podcast collection.

Subscribe on iTunes

Subscribe on Acast

You heard from Vicky, at Starnash guesthouse, in the podcast. I met Vicky as she tended her seedlings, and here she explains why ‘going to seed’ is no bad thing for the veg patch:

Climate change is so evident now. There is no getting away from it. Here in my little patch of Southeast England the weather is beautiful as I write, 26°C in late April. The leaves on the old field oaks are just beginning to appear giving the frizzled twigs an airbrush of bright green. Blossom is appearing on the apple trees and on the surface it all looks perfect. But we know it isn’t.

We know we’ve only got a decade to do something before there is no going back. The beauty of this balmy day is tinged with unease, We’ve all got to take responsibility now, every single one of us, in all sorts of tiny ways to pull on the reins of climate change. It seems like a long shot, but there is always hope. Hope lies in the germination of seeds.

Where ever there is a natural disaster, war, a nuclear meltdown, it is the seeds that break through that devastation from seemingly nowhere soon to cover barren landscapes with new life. Seeds are remarkable. You only have to hold a single tiny seed in the palm of your hand to envisage the wealth of beauty or nourishment that will spring forth from that seed with just the application of a little water when placed in the soil. We can’t actually watch a plant grow with the naked eye, but think of how a single pumpkin seed romps across the vegetable patch sending out tendrils and saucer sized spiky leaves, it’s hefty fruit swelling like Buddha bellies in just a few weeks.

Plants are generous beyond compare. Leave them to go to seed and that is exactly what they do, producing hundreds if not millions of seeds to drop into the soil and germinate in precisely the correct conditions to produce another perfectly formed plant. And so the cycle goes on.

Well, it goes on unless humans mess with it and modify it with suicide genes that stop the seed from reproducing true to form the following year. This has some great economic advantages for certain seed producers because many of these hybridised seeds have to be purchased from the seed company that holds the patents to that particular seed variety.

Seed security and the ability of seeds to reproduce true to form is one of the most important issues that we face in the future. Seed banks are some of the most secret and protected buildings, built to withstand earthquakes and nuclear attack in order to safeguard our future food supplies. The gardener of olden times knew how to save seed to produce fine crops year on year.

There is nothing like growing your own food for satisfaction and good health but knowing the seed that it is grown from is very important too. Always try to use “open pollinated” seeds – these are the ones that will reproduce true to form every year.

You can save seeds by letting one or more of your plants go to seed at the end of the cropping season and collecting and storing the seeds, but if you want to be lazy about this and work with nature, just let the seeds drop into the earth. They will germinate at exactly the right moment if the conditions are right, saving you from buying lots of seed and potting compost from the garden centre and laboriously tending your seedlings in the greenhouse.

Instead, all you have to do is pull out the unwanted seedlings from your vegetable patch. Its most satisfying watching nature do her own thing and knowing that in some way you are taking steps to protect our food security in this climate of change.

Don’t forget to share your seedlings with friends and tell people that they come from open pollinated seed and that they too must collect and share the seeds from their plants. This way we spread the word and the will to act against climate change.

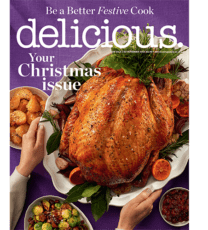

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter