1999: the year that transformed British food forever

It was the cusp of a new millennium and the world of food was about to get a shake-up, the repercussions of which would continue to be felt decades later.

Katy Salter surveys the people and events that made 1999 a year of such profound and long-lasting influence.

April 1999: a 23-year-old chef slides down some banisters, roasts some lamb, says ‘pukka’ several times… and changes Britain’s relationship with food. Jamie Oliver’s first series, The Naked Chef, began with these words: “Cooking’s gotta be simple. It’s got to be tasty. It’s got to be fun.”

It was a manifesto for a new way of cooking: one that reclaimed food from Michelin-obsessed chefs and competitive dinner parties. Yet no one could have predicted just how much of an impact Jamie would have over the next 20 years.

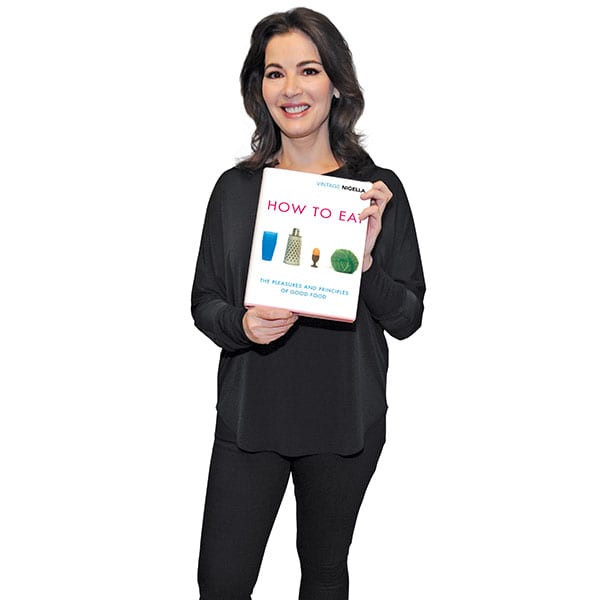

It was a momentous year for food. Nigella Lawson’s How to Eat was a huge hit. River Cottage made its TV debut just as the mantras ‘eat local’ and ‘eat seasonal’ were taking root. Few people could have realised it – distracted as we were by the Y2K bug, Britney Spears and The Matrix – but the stage was being set for the thriving British food culture we have today.

The roots of the revolution

British food was in a strange place. The fall-out from the salmonella scare of the late Eighties put consumers off British eggs. The BSE (‘mad cow’) crisis affecting livestock made headlines throughout the 1990s. “Public trust slowly eroded as a series of food scandals got into the news. BSE was the last straw,” says Tim Lang, Professor of Food Policy at City University London.

The European Commission imposed a worldwide ban on British beef exports in 1996. Morale was low among farmers. “The people who really suffered were the small beef and lamb producers. There were a lot of regulations, their markets collapsed. It was pretty grim,” says Martin Orbach, co-founder of the Abergavenny Food Festival.

Conversely, the restaurant scene had never been more exciting. The British food revolution started in restaurants including Aubergine, where Gordon Ramsay won two Michelin stars in 1997. He opened Restaurant Gordon Ramsay in 1998, followed by Pétrus in 1999.

Telly chef Tom Kerridge remembers 1999 as an exciting year: “I was working at Rhodes in the Square, and it was at the peak of Gary Rhodes’ notability. And Gordon Ramsay was making a huge name internationally.” Heston Blumenthal won his first star in 1999 at The Fat Duck. London gastropubs such as The Eagle were buzzing, as were St John, Moro and The River Cafe.

The Naked Chef goes big

Run by Ruth Rogers and Rose Gray, acclaimed London restaurant The River Cafe was where Jamie got his big break. When a documentary about the Italian restaurant aired in 1997, TV producer Pat Llewellyn was watching. She was drawn to the cheeky sous-chef in the background and signed him up for The Naked Chef. TV bosses weren’t at first convinced. The BBC Two show sat unaired for months, and viewing figures only took off near the end of the series. But when it went big, it really went big.

“It was overwhelming,” says Jamie. “People used to shout at me in the street. It was nuts! Who would have thought I’d be asked to cook at Number 10 for Tony Blair? Or that I’d hear Zoe Ball on the radio saying she’d cooked Fatboy Slim my seared tuna for dinner?”

So, what was special about Jamie? For starters, he believed good home cooking wasn’t about replicating restaurant creations. “Even though he cooked professionally, he still understood what it was like to be a time-pressed home cook,” says food writer Bee Wilson.

Jamie wore casual clothes, not intimidating chef’s whites. His style was a huge departure from shouty-chef shows and more prescriptive cooks like Delia Smith. In the first episode of The Naked Chef, he rustled up a wonderful relaxed dinner for friends on camera: roast lamb followed by baked fruit with mascarpone. There were glugs of olive oil, and ‘loadsa herbs’. Jamie’s food was about having a go.

Cook turns campaigner

Jamie also got men in the kitchen. “Before Jamie and Nigella, cooking seemed functional, serious and a little sexist. Men were chefs, women were home cooks,” says delicious. regular Georgina Hayden, who worked for Jamie Oliver as senior food stylist for 12 years. Seeing an Essex lad rustle up a risotto, and sell millions of books in the process, helped shift that perception fast.

Says Jamie: “I remember some great big geezer shouting at me in the street. My life flashed before me, but he said, ‘Thanks to you, I’m in the kitchen three nights a week cos my missus says if that blond boy can do it, so can you!’ Then he said, ‘I really enjoy it. I think I’m a good chef!’ Those personal stories make me feel proud of those early years.”

Twenty years on, Jamie has written 22 cookbooks and sold more than 43 million copies globally. There are apps, branded products, a restaurant empire (which has had mixed fortunes) and, of course, Jamie the Campaigner: hiring disadvantaged youngsters at his restaurant/social enterprise Fifteen, taking on the Government over unhealthy school dinners and sugary drinks, and encouraging us to buy free-range chicken. Back in 1999, however, he was one of many putting the joy back into cooking…

The Nigella effect

Before Nigella was a TV cook, she was a writer. In 1998, she published How to Eat, an ode to home cooking. It was a huge hit, selling 300,000 copies, and stood out on shelves crowded with cheffy tomes. “TV chefs set an artificial standard. People felt cooking was a kind of performance they might be judged harshly on,” says Bee Wilson.

Nigella urged us to find confidence in the basics: stock, roast chicken, flavourful stews and rustic bakes. “She was radical in defining home cooking as something that didn’t need to apologise for not being ‘cheffy’ or professional. She thought home cooking could be something even better,” says Bee.

In 1999, Nigella signed a TV deal (Nigella Bites aired in 2000) and began writing a second book: How to Be a Domestic Goddess. It was another smash, kickstarting the Noughties baking revival. “Nigella brought global influences into British baking while understanding the sturdy comfort of a Victoria sponge,” says Bee Wilson. Then there was the ‘Nigella effect’, as she caused sales spikes of products after using them on her shows. “Nigella increased sales of goose fat, Kenwood mixers and maple syrup, to name a few,” says Sarah Edwards, director of trends at food and drink trend-spotters The Food People.

From farming to festivals

At the same time, a seasonal and local food revival began. “The arguments for localism and seasonality grew in the 1980s and 1990s,” says professor Tim Lang. Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, who had also cooked at The River Cafe (“He was good, but he made a lot of mess,” said Ruth Rogers), helped these concepts become popular when Escape to River Cottage aired in the spring of 1999. Hugh’s exploits – rearing pigs and growing veg – were fun to watch. Brits were rediscovering the joys of seasonality and the merits of home-grown meat and dairy.

Britain’s first farmers’ market opened in Bath in 1997 and London’s first was in Islington in June 1999, thanks to enterprising American Nina Planck. “I found 14 farmers willing to take a chance. It rained the first day, but the place was mobbed. There’s a picture of me buying the last carrot,” she recalls. There are now 21 farmer’s markets in that group. Borough Market’s transformation into a destination for food lovers started in 1999 too, with the establishment of a monthly retail market.

The export ban on British beef following the BSE crisis officially ended in August. In September, farmers Martin Orbach and Chris Wardle held the first Abergavenny Food Festival. “We wanted people to meet farmers and have fun, and become better informed at the same time,” says Martin.

The first festival had 3,000 visitors. Now it hosts 30,000, and food festivals are a staple of the British summer, reflecting the elements that have changed our food culture.

“In the past 20 years, we’ve taken a keener interest in food,” says Richard H Turner, executive chef at London restaurants Gridiron and Hawksmoor. “We’ve seen the term ‘foodie’ become commonly used.”

As a new millennium beckoned, our food culture was in a better place. Pride in British produce was returning after a tough decade. Interest in local food was growing rapidly, thanks to farmers’ markets and festivals, and a new generation of celebrity cooks – Jamie, Nigella and Hugh – were putting the fun back into home cooking. As a young Jamie might have said, 1999 was pukka as years go.

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter